Per-Hjalmar and Luppa-Britta-Aset

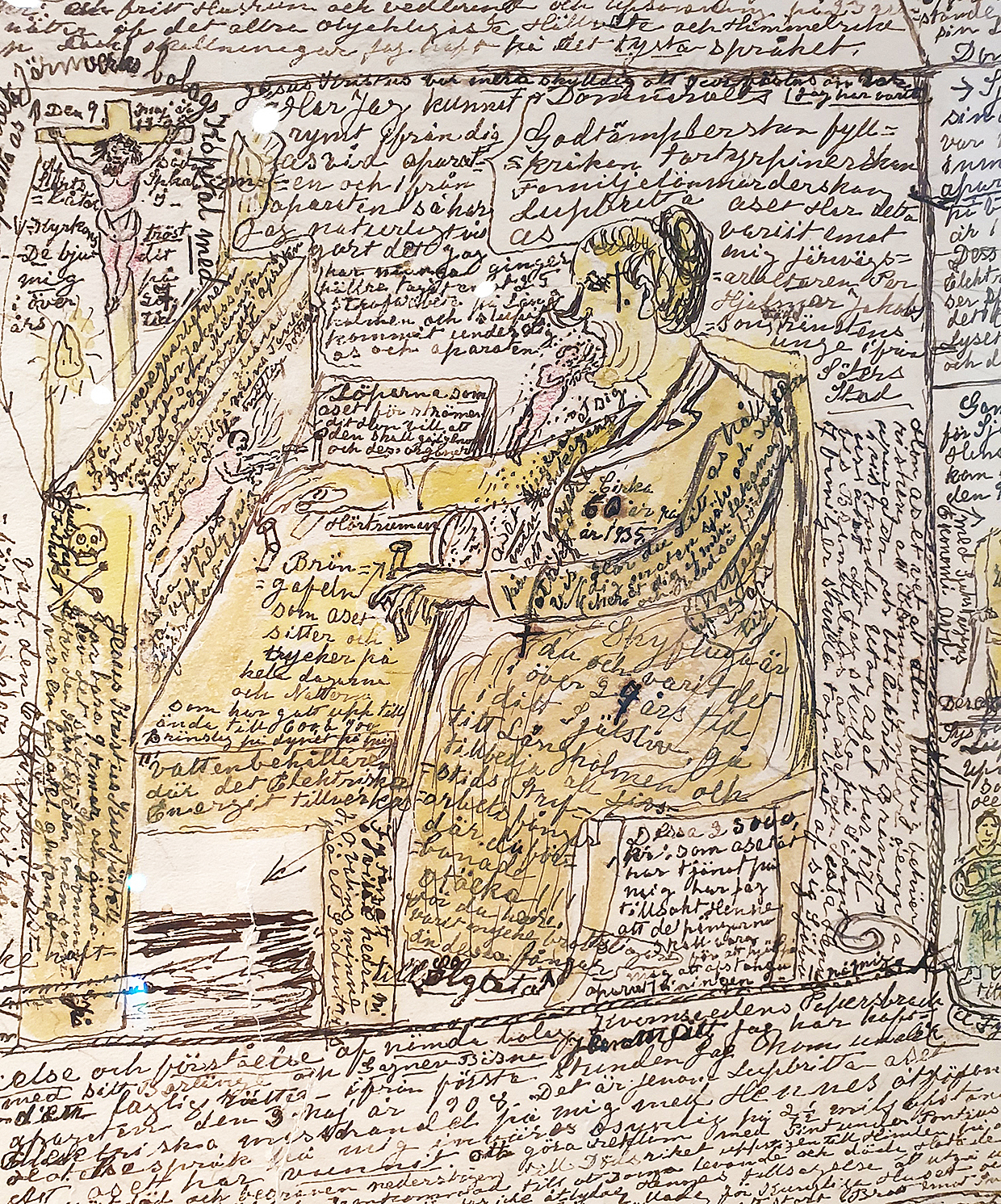

Per-Hjalmar, a patient at Säter’s hospital, leaves behind one of the most extensive collections of works that we know of in Sweden. Originally from Borlänge, he was admitted to the hospital in 1912, the same year the hospital was opened. His surviving work spans a large number of letters and drawings, often executed as if in a diary like format. Per-Hjalmar fills in all surfaces with text, drawings, diagrams or found images. A kind of horror Vacui, where all voids must be filled. The drawings are made on the material he came across at the hospital. Letter paper, cardboard discs, almanac backs, anything useful he drew and signed. In the paintings and letters, the concepts of time are relative. It is 1908, 1910 and simultaneously 1930s and 1940s. Therefore, it is difficult to know exactly when a picture is made and finished. In the drawings, an early 20th century Sweden emerges. Per-Hjalmar talks about the rise of the labor movement, Hinke Bergegren and Kata Dahlström visit the mills in Dalarna and also draw the horrors of the First World War. He reads newspapers and is well aware of world developments.

A central figure in his works appears in 1920. Her name is Luppa-Britte-Aset (LBA). In a way that is very typical of individuals with paranoid delusions, his tormentor LBA is situated in an unknown place where she plays her pain organ, which through the electricity and lights in the ward transmits a kind of energy that affects Per-Hjalmar very badly. His only way to escape its power is to lie in water, so he often has to lie in the bay below the hospital to get some relief. The pain organ is a fascinating and archetypal image of the notion of mind control machines, something that is earliest documented at James Thilly Matthews’ Air Loom in the 18th century. An exhaustive and fascinating text on the subject is Victor Tausks “On the origin of the influencing machine in schizophrenia” The author August Strindberg describes in the book Inferno how he is convinced that the neighbor has a machine that controls the weather. How Per-Hjalmar arrived at the pain organ is unclear, but many patients were also unaccustomed to such things as telephones, loudspeakers and electric lighting at the beginning of the 20th century and could be strongly influenced by this.

Per-Hjalmar has several traits that are iconic phenomena in outsider art internationally. He was of course not aware of this but is closely related to the work of well-known outsiders such as Henry Darger, Jacob Mohr and Adolf Wölfli. It is fascinating to note how certain traits and expressions within what is called outsider art recur, as if there were styles, despite the fact that the creators never had knowledge of other outsider creators. This is not the place to speculate too much about this but Jung’s ideas about a collective unconscious are close at hand when you see strong similarities between various outsider artists through time and space.

Per-Hjalmar and Luppa-Britta-Aset

Per-Hjalmar, en patient på Säters sjukhus lämnar efter sig en av de mest omfattande samlingarna av verk som vi känner till i Sverige. Ursprungligen från Borlänge togs han in på hospitalet 1912, samma år som sjukhuset öppnades. Hans efterlämnade arbete spänner över ett stort antal brev och teckningar, ofta utförda som i dagboksform.

Per-Hjalmar fyller ut alla ytor, med text, teckningar, diagram eller funna bilder. Ett sorts egensinnig Horror Vacui, där alla tomrum måste fyllas. Teckningarna är utförda på det material han kom över på sjukhuset. Brevpapper, kartongskivor, almanacksbaksidor, allt som var användbart tecknade och skrev han på. I tavlorna och breven är tidsbegreppen relativa. Det är 1908, 1910 samtidigt 1930-tal och 1940-tal. Därför är det svårt att veta exakt när en bild är gjord och avslutad. I teckningarna träder ett tidigt 1900-tals Sverige fram. Per-Hjalmar berättar om arbetarrörelsens framväxt, Hinke Bergegren och Kata Dahlström besöker bruksorterna i Dalarna och tecknar även första världskriget fasor. Han läser tidningar och är väl insatt i världsutvecklingen.

En central gestalt i hans arbeten dyker upp 1920. Hennes namn är Luppa-Britte-Aset. På ett sätt som är mycket typiskt för personer med paranoida vanföreställningar så finns denna plågoande på en okänd plats där hon spelar på sin pinorgel som genom elektriciteten och lampor på avdelningen sänder en sorts energi som påverkar Per-Hjalmar mycket illa. Hans enda sätt att komma undan dess kraft är att ligga i vatten, så han får ofta ligga i viken nedanför hospitalet för att få lite lindring. Pinoorgeln är en fascinerande klassisk bild av föreställningen om medvetandekontrollmaskiner, något som tidigast finns dokumenterat hos James Thilly Matthews Air Loom på 1700talet. En fascinerande och omfattande skrift på ämnet är Victor Tausks “On the origin of the influencing machine in schizophrenia”. Författaren August Strindberg beskriver i boken Inferno hur han är övertygad om att grannen har en maskin som kontrollerar vädret. Hur Per-Hjalmar kommit fram till pinoorgeln är oklart, men många patienter var också ovana vid sådant som telefoner, högtalare och elektrisk belysning i början av 1900talet och kunde påverkas starkt av detta.

Per-Hjalmar har flera drag som är ikoniska fenomen inom outsiderkonsten internationellt. Han var naturligtvis inte medveten om detta men är mycket besläktad med verk gjorda av välkända outsiderkonstnärer som Henry Darger, Jakob Mohr och Adolf Wölfli. Det är fängslande att notera hur vissa drag och uttryck inom det som kallas outsiderkonst återkommer, som om där fanns stilar, trots att upphovsmakarna aldrig hade kunskap om andra outsiderkreatörer. Det är inte platsen att spekulera för mycket runt detta men Jungs idéer om ett kollektivt undermedvetet ligger nära till hands när man ser kopplingar mellan olika outsiderkonstnärer över tid och rum.